How to Avoid Failure in Your Agile Retrospective

You need to be signed in to add a collection

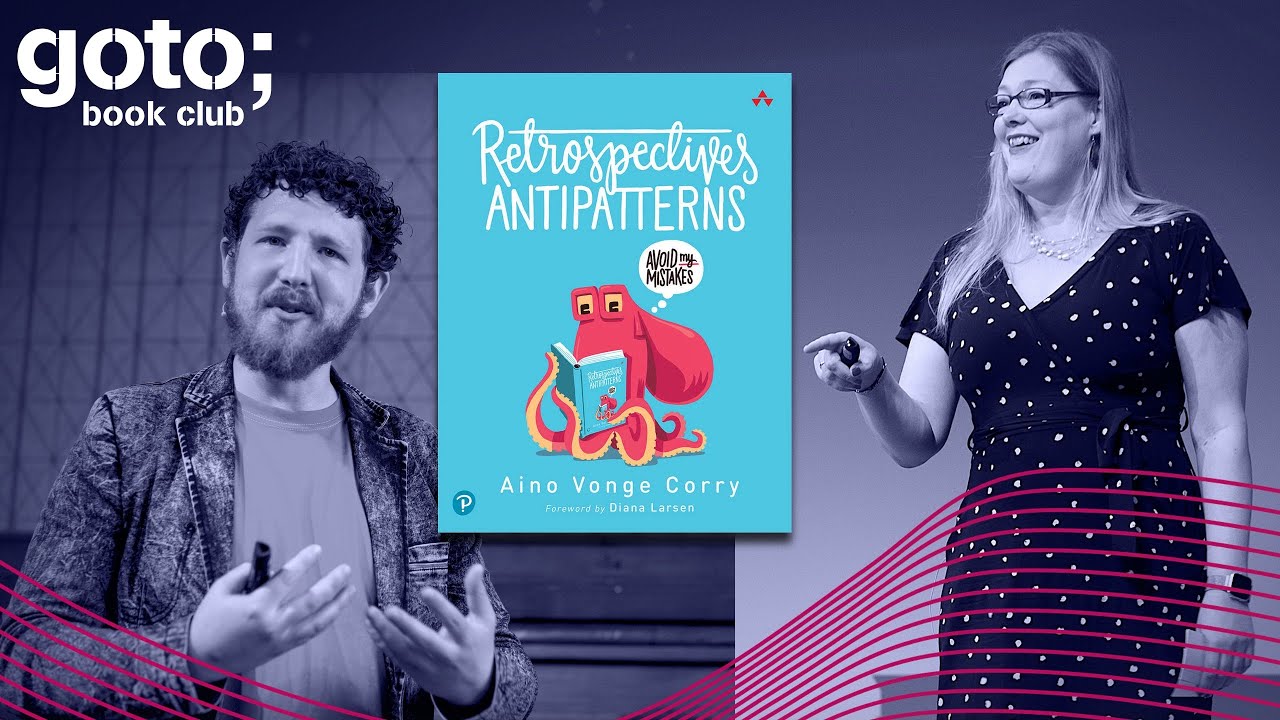

Running retrospectives can be intimidating, especially if you’re just getting started. However, their importance in shaping teams cannot be contested. To ensure that you run successful retrospectives it is essential to understand what common pitfalls or antipatterns appear while running them. Moreover, in the second episode, based on the book “Retrospectives Antipatterns,” Aino Vonge Corry and John Le Drew highlight the role of the facilitator as a team psychologist and what future retrospectives can do for you.

Transcript

Running retrospectives can be intimidating, especially if you’re just getting started. However, their importance in shaping teams cannot be contested. To ensure that you run successful retrospectives it is essential to understand what common pitfalls or antipatterns appear while running them. Moreover, in the second episode, based on the book “Retrospectives Antipatterns,” Aino Vonge Corry and John Le Drew highlight the role of the facilitator as a team psychologist and what future retrospectives can do for you.

If you missed the first part of the conversation you can find it in this article.

Antipatterns “Suffocating”

John LeDrew: Yes, I think it's a really interesting idea that needs to be able to name things. That's certainly something that I've taken from the book, looking through to be able to go back and to be able to actually use these terms to describe these situations more tangibly. And that's something that's really valuable. I think there are a few of the ones that really stuck out for me. Maybe just because of your sense of humor as much as I know.

Aino Vonge Corry: Oh, thank you. I can't wait.

John LeDrew: So I really enjoyed the description for... I'm just gonna try and skip to it quickly. I have the book right here and I'm trying to skip to it so I can find the exact description of it...

Aino Vonge Corry: Luckily, it's a short book so it's easy.

John LeDrew: Yes It was the one that I liked. I think it was suffocating. And what I liked about suffocating was, in which team members get tired and hungry, and unfocused during the retrospective, and the facilitator makes sure to feed them and give them oxygen so that they can concentrate a bit more. I've definitely brought biscuits to retrospectives before and cake. I have occasionally brought lunch and other things, general sustenance. Never before if I brought oxygen masks, though, not yet. And I'm just wondering if that was from a specific case?

Aino Vonge Corry: Yes, I can see that maybe I should have reworded that a bit.

John LeDrew: No, I like it. I like it.

Aino Vonge Corry: It's difficult to do something about it now when everything is online. You can't really change people's environment. The thing I have about that you don't prepare enough disrespect of preparation, that you don't prepare enough for online retrospectives in that email that you send to people, just before the retrospective where I remind them to get some coffee and probably have a bio break if they need it, that's part of that suffocating in a sense, to try to make them aware that we are still buddies, even though we're only using our brains most of the time at the moment. I definitely remember meetings that drag out and people are getting more and more tired and hungry and hungry, and things are just spiraling down. Another problem is also if you're the one standing up all the time, then you don't notice how the oxygen is leaving the room because you will get enough oxygen standing around huffing and puffing, but everybody else is sitting down getting more and more sort of tired.

John LeDrew: That's interesting. In a way, oxygen is an analogy for energy for you in that...

Aino Vonge Corry: It is.

John LeDrew: I just realized that when you mentioned it. I think because that's something that I found really interesting as a facilitator is a fact that you kind of get or at least I somehow find energy in the room when I'm facilitating, and I almost don't feel tired while I'm facilitating, even if I'm going all day doing.

I was facilitating a big 100-person, 2-department retrospective thing recently. I remember, it went all day. And it's 100 people. There were lots of people management and shuffling people around. There was only me, obviously, sole facilitating this thing. So by the end of the day, I was a bit dead, but I didn't feel it until I got home, which was still an hour's journey from the venue we were at. I remember getting home and I think I sat down on the sofa, just to kind of got in the house, and in fact, I think I just fell asleep. But I found that's a really interesting observation that you don't notice that because you're stood up and you're moving around, you know, just the energy.

Aino Vonge Corry: The adrenaline keeps us going. But also if we are standing up and they're sitting down, the difference is perhaps telling about who will notice the lack of oxygen in the room or energy in the room quickest.

John LeDrew: What are other things that you've done to help manage energy. I tend to get people to move around just randomly sometimes.

Aino Vonge Corry: I tend to do that as well. But randomly that depends on how well I know the team and who they are. I think perhaps as a woman in IT, not that I'm complaining because I'm having a grand time as a woman in IT. But as a woman in IT with the new team of very serious hardcore coders. It is my experience that you have to have a reason for all those things that you asked them to do. So if I want them to get up and move around or say something, I need to have a reason for doing it. Of course, I don't do it unless I have a reason for doing it. So I can say that "We need some more energy in the room so please just get up." But I would probably at least with the new team or if they're very serious, I would word it like, "In order for you to still have your attention going and your brains working, we should get up now and do something like this."

And then if I know the team and they're okay with me just doing weird things because they know it's in their best interest and not just because I take secret pictures and put them online when they look stupid, right, then I can just say, "Okay, now we get up and go around the table and then we see if we get in the same chair if we get in another." Or if we have an online meeting, I'd be like, "Go up and find something red and then show it to everybody else." Finding something red for me is pretty easy because I'm almost always wearing red. I have red glasses and a red watch and everything. So, I'll probably choose a different color. But you know what I mean.

John LeDrew: That's interesting. One of my facilitator that I trained, a client, she does yoga all the time. And she would basically between every, kind of, section within the retro would just be like, "Stretch." Yeah. The funny thing is that the team knew her far better than they knew me because that she had been working with them for five, six years, or something, and I was a new intruder. But they didn't know her as like a crazy facilitator, they knew me as the crazy facilitator. And then they were kind of- I remember them commenting on all that, it was gonna be great when, you know, I'll call her Julie, when Julie does the retrospective because we don't have to do any of that mad crap that John makes us do. The first thing she did was get them to do yoga or something or meditation or something. I remember the faces were gold.

Aino Vonge Corry: Yes. It's as if when we're grownups and going to work, it's not okay to understand that our body is also really important, stretching and realizing that we need to go to the toilet and have some water, but also that little brain residue that you have in the brain when you go from one meeting to another, there's always something in the brain that's sort of still there. And if you really want to concentrate on a meeting, you should have some sort of mindfulness first. If it's a team that I really trust and they trust me, we can just have, I mean, real mindfulness. When I say, "Just close your eyes for a minute and just be completely quiet for a minute. And then just think about what you're about to start with or think about nothing."If I can't do that, then I try to have that mindfulness moment just asking everybody the same question then going in around and having them answer that.

Also, depending on what kind of team I have, sometimes ask them, "What was your last meal? That's really boring if it's in Denmark because everybody eats the same. But if you have, like, a global meeting, then that can be very interesting. As I say to people, you can always lie. I mean, if you're ashamed that it was McDonald's, just lie. It doesn't matter. But just thinking about something else will sort of taking that brain residue away, and will make their brains fresh for the new moment. But that's something I'm thinking about. I thought even more about it when I started researching how people learn when I started teaching the teachers at the university. I found that interesting how you can accommodate people in a sense that makes it easier for their brains to get new material. You can also destroy the possibility for them to learn something if you know what to do.

Antipatterns “Naming things”/ “Affinity mapping”

John LeDrew: Yes, I've always found that when you're coaching, generally, or creating a learning environment in a retrospective or any other situation is obviously, learning is just foundational and teaching is foundational. Even outside of a formal academic institution.

There are those differences and the ways different people approach and absorb information. The thing I found interesting is that when you're teaching something like computer science, or when you're teaching engineering, or you know how to build web services, or whatever it might be, it seems like you're just trying to transfer information. And it's actually really easy just to give loads of information to somebody. In fact, they can do it themselves without any help from either of us.

But understanding (the information) is a very different beast. That's where it's coming back at your naming things. I found one of the exercises I actually do in retrospectives. I think we've done a similar thing. It's around affinity mapping when you're grouping the topics. One of the most important things around that is actually getting them to name the groups. So what I want you to do is obviously somebody described normally and discuss it as yourself. What are you going to name that group? Because that's gonna be the focal point for the conversation. And if you find it hard to name, then maybe it's different groups. And does that really summarize it?

You get them to really think about the naming. You can see some people, just their head start to overheat when they're struggling with it. But it's always the most valuable part of the exercise. I find it's the bit that helps enjoy the focusing. But then I often find that that's also the most challenging, and can be the most challenging part to facilitate for me anyway, just because people often disengage when they feel their brains warming up if you've noticed that.

Aino Vonge Corry: Yes, I've noticed that. It seems to me like brains are lazy. Right? And it seems also a bit like it hurts or demands too much energy to change your brain, which is the same as learning something. That's the way I think about learning is to change your brain.

Then sometimes people avoid that energy console or the pain or whatever it feels like to them. It's interesting, as you say, to see them reacting to a simple exercise like that by disengaging, because it feels uncomfortable for them to actually learn something. I think that the thing about affinity mapping and giving those different groups and names, so is this the process? Is this communication or is this technology? What is this really? It's a very good way for them to talk together and to learn together about what are these different symptoms? What is actually the problem behind it? So in a sense, it's also a bit of a course analysis, which can be very difficult, especially if you're not really that keen on seeing the results on that course.

Antipatterns “The Curious Manager”

John LeDrew: Indeed, especially when they're often challenging things, that kind of organizational things or challenging things that they don't really want to do or they often feel powerless to do things about them. One of the interesting ones in there is obviously the curious manager. I found that what interested me specifically about that was that I've seen both sides of that problem, which is that I've seen teams whereby they have, absolutely, by the book, the curious manager that I would rather not have him present.

This is maybe still part of the symptom, but I think it's on their journey to becoming more autonomous, is teams that felt and wouldn't actually discuss anything, really, of any value unless their manager was present because they felt like everything that they could do needed his approval to be able to date. It's like, "Well, we can't make an action, you know, without Mr. Manager here because he gives us actions. They give us the actions."

I've seen both of those things where I realized that the manager needed to be there at least temporarily, in order to create the safety for them to have those conversations. But I don't know if you've experienced a similar thing with that.

Aino Vonge Corry: Yes. I have. I've experienced it in several layers, so to speak. And one of the things that I often see is that if you have a team that has some problems that they keep cropping up popping up with different symptoms, then it could very well be one of the issues that you talked about, that it's the organization or it's something the manager has decided that they can't do anything about. And in those cases, I'm asking the team, "So do you want the manager to be present at the next retrospective or perhaps do you want the manager to be present at the first half or the last half of the retrospective?" Or sometimes I asked them, "So do you want me to take these three post-it notes and give them to the manager to figure out what level are we on here?"

Then I've had huge backslashes from the team sometimes where they said, "Oh, but we want our manager there. Our manager is our friend. It would be stupid. Why wouldn't we want our manager there?" And I'm like, "No, no, no, why wouldn't you want your manager there? Perfectly fine." In some cases, it was because it was a startup and they started together, and he is actually part of the team or she is part of the team. But it could also be in some situations where they don't really feel safe to say no to having the manager there. Then you have a different problem, right?

John LeDrew: I had an interesting one with a client that was a very big, old company, very, very hierarchical culture but what's interesting was that while the organization was still very hierarchical and very affected by old school, scientific management, so to speak, the lower tiers because of the regeneration program were different. The whole reason I was being hired in the first place was actually those kinds of middle tiers of management were far more progressive and far more, kind of, open. What was really interesting was that you have this interesting problem where the managers themselves were, kind of, completely safe to have in a retrospective really because they were, completely there from a kind of, "I just wanna listen and I just wanna..." Literally, as in not that curious manager as in I wanna mess with things, but literally, I will be there, and I will help, and they will really work, you know, they were great. But actually, the team would still perceive them as the same way regardless of everything because they're so affected by the past realities that were very, very real for them. I found that quite, quite interesting really, just, kind of, those differences.

Aino Vonge Corry: It is interesting because it's sort of a sort of dissonance that there's a distance between how the manager perceives it and how the team perceives it.

John LeDrew: Yes, absolutely. The challenge between how their manager would see themselves as this wonderfully safe, "I'm just here as," you know, and then the team see them as exactly the same person that has always been in that position. Do you know Tim Ottinger?

Aino Vonge Corry: No.

John LeDrew: I remember we had a conversation once about doppelgangers and this idea that you're rehearsing when you're gonna have a really difficult conversation with somebody and a you know it's gonna be challenging. And you rehearse it in your mind, that thing where you, kind of, have the argument in your mind, but the person you will imagine this person you're gonna have this argument with or whatever is often like 10 times worse than that person ever would be in real life. They're like, screaming at you, and probably getting violent, whatever else in your mind. And in your imagination, you've done everything from, kind of, cower in the corner, sobbing to dramatically storming out and standing at the door, like, some kind of, you know, with a big Hollywood exit. And you've done all of the ranges of things.

Retrospectives are indispensable for continuous learning and improvement in Lean, Agile, DevOps, and other contexts, but most of us have suffered through at least one retrospective that was a waste of time, or worse. Now, leading agile coach Aino Vonge Corry identifies 24 reasons that retrospectives fail and shows how to overcome each of them.

In reality this person's completely just fine, you know, a bit of a stern conversation that's over and you come out feeling great. But that doppelganger idea is there's the real person and then there's the imagination, the image of that person. What we were talking about was how you might have this situation where a previous manager, someone in a role, has actually left the company. A new person is now in that role, who is very different from that previous person. But the memory of that other person in that thing is still present. It's still affecting people. I think it's a really interesting challenge because actually, see, we're talking about retrospectives. Actually, I find that leadership structure... I mean, retrospectives are all about guiding teams. In fact, that's the main anchor point for autonomous teams in many ways. It's the main thing we do to change and to adapt its foundation.

Aino Vonge Corry: And it gives you team building and team understanding and everything. I think it's interesting how, as you say, that people react to the role and not to the actual person. So if they've had a bad experience, then that is sort of the signals that they get from their body. They probably get anxious when they used to get anxious in that situation.

Future retrospectives

Aino Vonge Corry: That's one of the reasons why I find it so interesting with a new team to make a future retrospective at times. So a future retrospective is where you draw a timeline from now until when the project ends, or Christmas, or a few months in the future. And then you say, "Well, imagine that you're here in the future and then what happened," then put the red, green or yellow post it notes, the things that were great on the green, the things that were bad on the red ones, and the question marks or the things that were in between under the yellow ones. I think I said that wrong. It doesn't really matter. The green one are good, the red ones are bad, the yellow ones are question marks.

Then people say first, "Well, it doesn't... I mean, we can't predict the future. Why are you making this do that? That's really stupid." And I say, "Well, try to do it anyway. Let's try to do it." And then once they get started, they warm up to it normally. And then we have this wall of things, this went wrong and this was good. And then this person got fired, and we got a new person on the team or something like that. And then what you do there is that you say, "Well, these are actually the hopes and fears that you have for this work together. So what we should do is that we should try to figure out how we can make the green ones that you hope will happen actually happen and how we can avoid the red ones that you fear will happen, make sure that they don't happen."

That is actually not because I think they can see into the future, but because I want to know what they've experienced before, as you said. They have had these experiences. And if they had a bad experience, they're worried it will happen again. And that's why I do it often with a new team is because it gives me a way to look into the experiences, to look into their brain. If I just asked them, maybe they wouldn't have said it but this is a bit convoluted and subtle. So suddenly, they're sort of "telling us" about a lot of experiences they had that were good and bad. And I think that's an interesting way of learning about people.

John LeDrew: So you're looking forward and that encourages them to look backwards because obviously they can only predict the future with their past experience.

Aino Vonge Corry: Exactly. Unless I'd be really lucky with my team members in the retrospective. That's always what's happened is that they predict the future by looking back.

John LeDrew: Yeah, unless you find that you're miraculously with a team that are in fact, you know, psychic, and they can tell the future and...

Aino Vonge Corry: I mean, do you remember the time we had Nostradamus in our team and we did the retrospective?

John LeDrew: Exactly. Exactly. Just like, whoa, all right, well, that was inconvenient. This is just a trick to make you retrospect. God, you're a psychic.

Retrospectives are indispensable for continuous learning and improvement in Lean, Agile, DevOps, and other contexts, but most of us have suffered through at least one retrospective that was a waste of time, or worse. Now, leading agile coach Aino Vonge Corry identifies 24 reasons that retrospectives fail and shows how to overcome each of them.

Aino Vonge Corry: Stop thinking so much about the future, why don't you tell us what happened. Yes, and I think learning about people and the team members learning about each other is very valuable. But also that sort of points back to the thing you said about the manager, if they have a bad relationship with the manager and it's not that manager's fault, so to speak, or the manager's genuinely sweet and trying to help them, it's probably something in the past.

The team psychologist

John LeDrew: Yes. And it's very difficult to root those things out. It's really challenging. And that's when we end up moving into the role of, like, team psychologist. It sometimes feels like that, doesn't it?

Aino Vonge Corry: Yes sometimes it feels like that. And then you run into this cognitive dissonance that I find so interesting in brains that you can have this understanding of the world living perfectly in harmony with this understanding of the world. As long as those two never meet in the brain, you'll never find out that you actually have parts of your brains being completely disagreement with each other. And what you have to do then is you have to get it out in the open to make people understand that you actually believe this and this, and those two cannot both be true. It's something that I see in the teaching as well, a lot, where some students of mine, they come to a class like a programming class or something with an understanding that they had in their mind, which is wrong.

Then they go through my course, and I talk to them, and I have lectures, and they have exercise. And then in the oral exam, it turns out there that they actually had these two understandings, and then they'll say, "But you said that. I remember you saying that in one of the lectures." And I know I never said that in the video so I can look back. But it's interesting how the brain really wants us, in a sense, not to learn and wants us to stay in the past. That's one of the things that's really interesting with being that psychologist and the team is how can we work against that?

John LeDrew: Cognitive dissonance is a fascinating thing, isn't it? Because it's like, both our brains. It's like the least perfect defense mechanism ever. We build it as a defense mechanism, but then it creates massive internal conflict, that was almost what it was designed to try and avoid in the first place. You know, and we end up... I mean, I find what's been... What's really interesting with that, I've often seen is there is that problem around... Yes, even with things like, you know, whatever, making teams do silly things. And one of the interesting things around that is actually the, kind of, getting people into the child ego state, issues. And one of the things that's really interesting, I found a way around that is the perfect state to be in in a retrospective is that curious, non-judgmental child ego state where you accept everything.

It can be a really interesting thing where actually, most people can get there because actually, most people, even the most serious real proper grownups, you know, do play quite a lot. It's just, kind of... And that's their way of getting there. But it could be a real... What can actually be interesting is that you can see that it creates... For some people, it actually creates quite significant cognitive dissonance for them, especially in a work situation. Also the fact that it's like... You know, I think in the book, one of the stories you mentioned is around that it was, again, around that peekaboo thing around how one of the people that you mentioned had to keep this kind of complete work-life separation. You know there is no connection there at all. I also find that really confusing. I found that that thing is that when you try to do anything playful, in order to encourage people into that state, it can create this real problem if the identity that they have at work is a very fixed thing. I think that people tend to do that thing. They create identities for themselves in different contexts.

Aino Vonge Corry: They do. I guess it's because they're afraid. They are afraid that people will find out that they're actually just still kids with bigger shoes and house loans. Right? Because when I talk to people, when I teach teachers how to teach, and when I facilitate how to teach people how to facilitate, the analogy I make is often with... So with children, you do this. With children, you do this. Then at some point, there's always somebody saying, "Why do you keep comparing grownups with children?" Because they react in exactly the same way. They're just human beings. The reason why I make the analogy with children is because it's something everybody can understand. Even if they didn't have children, they have been a child. I push you again.

John LeDrew: I mean, they could have been placed here by aliens.

Aino Vonge Corry: Sure. And I think so.

John LeDrew: I've met a few people that I strongly suspect this to be true.

Aino Vonge Corry: You're actually one of mine, John.

John LeDrew: I find that it's a really interesting thing around that idea of the way we will react in the same way because something that I've found... And it's funny, it's kind of full circle, but we were talking about psychological safety. Something that I've found is that when people aren't psychologically safe they don’t feel safe, you're scared, you're fearful. It's something that I've come to realize is that you can fairly reliably map, like, almost all of the dysfunctions that you frequently see within a typical, professional environment, to fear reactions, you know, to fight, flight and freeze. That's especially true in situations where we're as facilitators creating uncomfortable situations often or creating, even if we're not doing crazy things with the team, we're creating a situation that is uncomfortable simply because we're encouraging them to learn, you know, over a career, or encouraging them to introspect, or to think about the team, or to think about a failure possibly, or to think about, you know, a potential failure, if it's a future perspective, which might be the way they look at it.

Why do we need retrospectives?

Aino Vonge Corry: Yes, we have to do that. We have to put them in an uncomfortable state because if this was so comfortable to them, they probably would just do it. Right? And they obviously don't, which is why we need retrospectives. So, my future hope is that people will actually talk to each other, share experiences, learn from that in a curious, and open, and positive way, and then we don't need retrospectives anymore.

John LeDrew: Or in fact, that would solve a lot of problems in society.

Aino Vonge Corry: Oh, yes. Don't get me started.

John LeDrew: I'm imagining this because on the day that we're recording this, in only a few hours, obviously, that a certain president is going to be departing the White House and the new one is gonna be coming in. And I'm just pondering now, in my mind, kind of, that particular president sitting down in a retrospective facilitated by one of us.

Aino Vonge Corry: I hope it's you.

John LeDrew: Thanks. Thanks. So I'll take one for the team. Just imagining what that would be, just, kind of, thinking about the last few years.

Aino Vonge Corry: Let's look back, can we learn from any failures? Did we say something that maybe hurt other people?

John LeDrew: Failures? Failures? No. No. You have to be very careful about the language in order to make that situation psychologically safe, I think.

Aino Vonge Corry: Definitely.

John LeDrew: Yes.

Aino Vonge Corry: So we have gone full circle now, John.

John LeDrew: One of the things that I found, going back to what we were talking about kind of the organization, and that specifically in the soup is certainly something that I found. Maybe this is where, as a coach, I'm frequently straddling this interesting line as a retrospective facilitator, which is that, in some cases, I am completely context free and I'm literally just some team somewhere in the world says, "Come do a retro," and I go into a retro. And I have no idea what the hell they're going on about and I'm just guiding them through to an outcome. They are my favorite retros because they're like, relatively stress free and they're, kind of, easy in some respects.

Then you have the other type, which is where I'm actively coaching this particular organization or team. I do know loads of the context because I'm probably working with them actively on something, either on a specific project or at least within that team and within, you know, their circumstance. Then what I find is that, while I can still facilitate because I'm never a team member, in the same sense, I'm very much straddling this line between context free facilitator and consultant, where I am looked upon to help solve this challenging problem. It's almost like they look to me for value for money, certainly, if the manager is hovering nearby, like, to present solutions or to help solve all their problems. I find that one of the things that I'm able to do in that context is that when they find themselves in the soup, the solution is often for me to take an action to go and do something about it. Because I might be able to go and march into the CEO's office and say, "All right, we got a problem here."

Aino Vonge Corry: You have an influence that they don't have.

Retrospectives are indispensable for continuous learning and improvement in Lean, Agile, DevOps, and other contexts, but most of us have suffered through at least one retrospective that was a waste of time, or worse. Now, leading agile coach Aino Vonge Corry identifies 24 reasons that retrospectives fail and shows how to overcome each of them.

John LeDrew: Yes, and that's useful and sometimes a burden, actually, I find because it can be difficult to... It can be... I feel like sometimes I'm in a situation where I'm creating learned helplessness, you know, to mean by accident because I end up going and solving it but rather than helping them be empowered to go and do the job. I'm wondering if you've seen similar things, where I think sometimes when you're in the soup, the only solution is to, kind of, for us to get our hands dirty, as a coach to help untangle or scoop them out if that's the better analogy.

Aino Vonge Corry: I agree. So, if they're confronted with a lot of their problems being in the soup, which are things that they don't have any influence on. Normally, what I say is that what you can do with these is that you can learn to live with it. You can learn to accept it, and you can adapt to that situation. But it's definitely true that sometimes these things would not be in my soup, they would be under my influence. And you should, of course, be wary of the learned helplessness. But I think that if you're aware of that as a facilitator, then you will be supporting them, and facilitating them, and sort of pushing them to figure out what is the most important problem for you to discuss right now? What are actions you could take, experiments you could try with this? And then in the cases where it is in the soup, then you must trust that they actually have emptied out any opportunity to gain influence on that, and then you can help them. Then I don't think you should feel that bad about doing that because I mean, there's always enough problems sometimes when I see them. But there's always enough problems.

John LeDrew: Indeed. Always.

Aino Vonge Corry: What I sometimes struggle with is not just solving their problems.

John LeDrew: Yes. I think there's always that pressure isn't there as a coach, especially because you're seen as that, kind of like, especially for when you're seen as technical as well. So, "Well, you could help them solve this problem." It's like, well, I could, but you don't want me to. Is what I normally say. But yes, we do. We've just asked you to. No, you really don't want me to solve this problem.

Aino Vonge Corry: Yes, it's a lion dance. Right? Sort of you have to stay there. At least I think in the axial retrospective, you should stay just as a facilitator and then you could say afterwards too, "Would you like me to offer you some help or some input on this?" But once you start solving their problems as a facilitator, then as you said, that's what they will expect you to do. And every time they have a problem, they say, "So what you would do with this, kind of, meeting, what you would do with these pull requests, what you would do with the code standouts? And that's not what you want them to do, you want them to grow as a team.

Antipatterns “Do it yourself retrospective”

John LeDrew: So, it's interesting as a facilitator, talking about that, actually. It's one of the things... You know, I've forgotten the name of the thing I wrote down and I've lost my bit of paper because I jotted down the ones that I wanted to talk about. There's one talking about when the facilitator is essentially, too involved with the team themselves and like...

Aino Vonge Corry: Is it like the do it yourself retrospective?

John LeDrew: Do it yourself. Yes. I think so. So when the teams are doing it themselves, essentially. That it means the facilitator is just too involved. That's something that I care a lot about. And I've often advised, set systems up where teams kind of facilitate each other's retros and they rotate facilitators and things. But it's often in a very big argument that I get from teams. "Oh, we can do it." Then you have two teams that go on about the ultra-efficient ones, where they do it themselves and they're over and done and dusted within half an hour. And they always come out with actions.

Aino Vonge Corry: Yes, they can be very efficient, interesting those retrospectives.

John LeDrew: It's really hard to comment on that because I feel like, "That's brilliant. Well, you don't need then."

Aino Vonge Corry: Yes, and I think in those cases, you can't really do anything about it in the moment. You just have to continue to give them a chance to show them what it can really feel like.

John LeDrew: Yes. I think, although interestingly, what I've found in some cases is I've gone and facilitated a correctly linked about 90 minutes or 2 hours retrospective to replace the half an hour. And then there's always, like, the three team members that thought, "Wow, that was so valuable and we got some stuff." And there's those who think, "God, we spent two hours in there.

Aino Vonge Corry: Yes, I think to evaluate the worth of the retrospective, it's not enough just to evaluate after the retrospective is done but at the next retrospective to see one of these experiments, which did you do and what did you learn from them? I think that's the only way to really evaluate and retrospective is to see the action points or the experiments, do you get them done? And what did you get out of them? And I think you will see this huge difference between a very efficient one and a good one.

John LeDrew: That's a really good point because that's something that I've always said actually to teams and they talk about how valuable. And I say, "Look, something to remember is the value of this retrospective or any other one is not here. It's what happens after the retrospective. It's what... You know, these are the actions you're taking out. Well, the effort you put into as a team, you're able to prioritize doing something about these. Well, that's what's gonna define how useful and valuable this is actually. The retrospective is valueless.

Aino Vonge Corry: In itself and nothing else happens. This is a good final statement for this interview. In itself, the retrospective is worthless.

John LeDrew: Absolutely.

Aino Vonge Corry: Don't tweet this out of context.

John LeDrew: She says retrospectives are worthless. Done.

The Octopus

John LeDrew: Aino, I just wanted to ask you, you've got something on your shoulder I think. Other shoulder, other shoulder, other side.

Aino Vonge Corry: It's an octopus. Yeah, she's the one who actually wrote the book.

John LeDrew: That's amazing I didn't notice it. Oh, right.

Aino Vonge Corry: Yes. And she wanted to be part of this interview. She's always with me like this. I just hadn't noticed it because it's so nice and comforting to have her here. It's nice to have a comforting octopus. People in the planes don't mind either.

John LeDrew: She goes straight through customs just fine.

Aino Vonge Corry: Oh yes, no problem at all.

John LeDrew: Yes. So that's her portrait from the book?

Aino Vonge Corry: That is her. She's called Scarlet.

John LeDrew: She changed the color though. I guess because she's dealing with antipatterns, it's red like angry for an octopus.

Aino Vonge Corry: Yes. She's always a bit angry in the book. All the pages, she's angry.

John LeDrew: I've been reading. Yes, indeed.

Aino Vonge Corry: Thank you.

John LeDrew: Thank you.