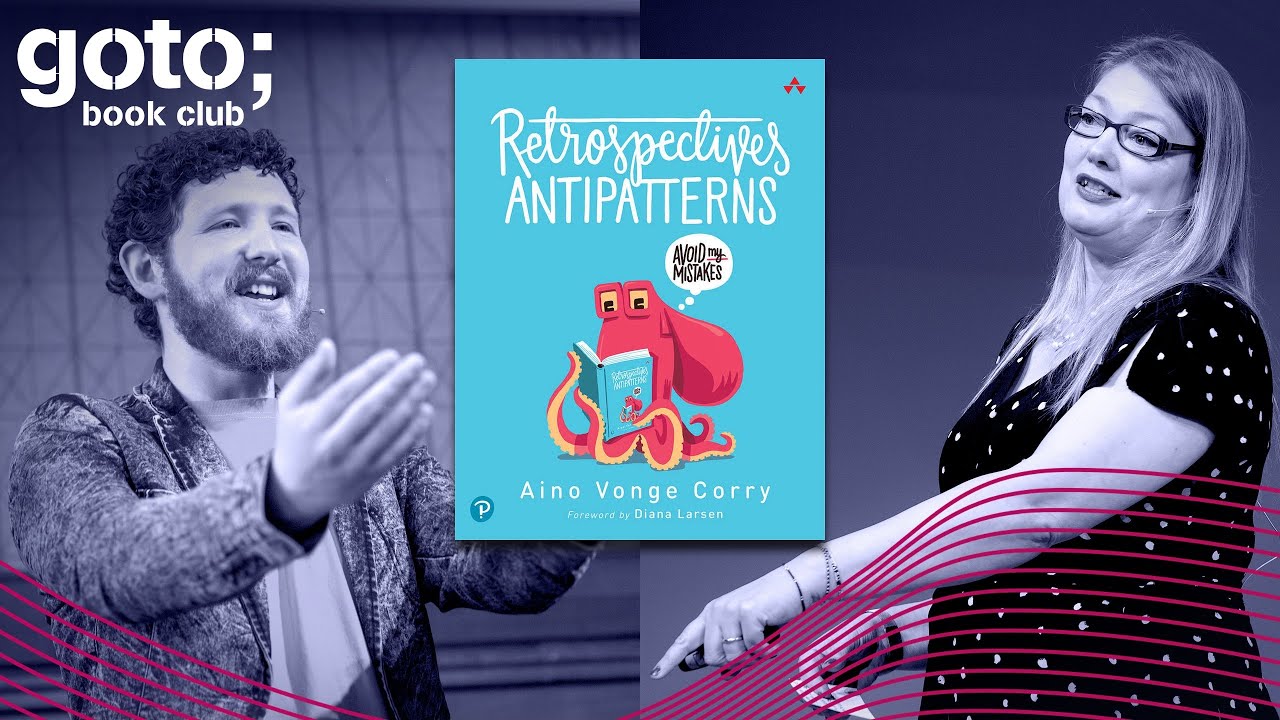

Retrospectives Antipatterns with Aino Vonge Corry

You need to be signed in to add a collection

Agile retrospectives are much more than just a quick overview and assessment of what has worked and what hasn’t worked. They enable teams to discover their internal mechanisms while sharing, appreciating and learning from what has happened. There are different ways and approaches to handling retrospectives, and in her book, Retrospectives’ Anti-patterns, Aino Vonge Cory highlights them by sharing from her own experience.

Transcript

Listen to this episode on:

Apple Podcasts | Google Podcasts | Spotify | Overcast | Pocket Casts

Agile retrospectives are much more than just a quick overview and assessment of what has worked and what hasn’t worked. They enable teams to discover their internal mechanisms while sharing, appreciating and learning from what has happened. There are different ways and approaches to handling retrospectives, and in her book, “Retrospectives Antipatterns”, Aino Vonge Cory highlights them by sharing from her own experience.

Discover why psychological safety matters, how to handle failures during retrospectives and why we need a common vocabulary to talk about retrospectives in this Book Club episode with Aino Vonge Cory and John Le Drew.

Stay tuned for the next episode "How to Avoid Failure in Your Retrospective."

John LeDrew: Hi, there. I'm John LeDrew, and I'm an agile coach.

Aino Cory: Hi, there. I'm Aino Cory Cory, and I'm also an agile coach.

John LeDrew: Wow, what a coincidence to just find each other here today. Both agile coaches, Wow. Well, hi, Aino. It's nice to see you.

Aino Cory: So nice to see you too, John.

John LeDrew: In strange circumstances, but it's still nice to see you. So, I believe that you've written a book.

Aino Cory: You're right. I have.

Agile retrospectives and psychological safety

John LeDrew: I know. And amazingly, for us just to bump into each other, I have a copy as well. And as I've known you a little while, I also know and you know, that we both have miraculously an interest in agile anti-patterns. I was just thinking back to when we... well, not when we first met, but when we met up, I think it was a GOTO Chicago a few years ago. What I found interesting was that I delivered a workshop on psychological safety. Then immediately afterward, I think the second day or the third day, you were doing a workshop on retrospective anti-patterns. I gatecrashed your thing because it was raining. I decided Chicago was best when it wasn't raining, although it shows how little I know about Chicago because I think that gives me about two days a year to actually see it.

But I gatecrashed, and what was really interesting was, firstly, I think three or four of the people that were in your workshop had attended mine. Something that struck me when I was in there was actually how much crossover there was between psychological safety and retrospectives for obvious reasons, I think. But could you maybe go into that a little bit because obviously, a huge amount of when I was going through the book, there is this underlying thing to me, which seems in almost all of the anti-patterns, that there's this underlying thread of safety being really important? And that's something that's really important to me and I was just wondering if you could expand on that a little bit?

Aino Cory: Yes, I think that first I have to say what I believe psychological safety isn't to me. Psychological safety is not to feel comfortable all the time, but to be comfortable even in uncomfortable situations, so that you can go into a situation where there's some sort of conflict or where there are people who disagree on things and you have to do something for the first time, and you can still feel okay with it. To me, that's psychological safety. I agree that there's a huge overlap with how to do good retrospectives. There are many ways of facilitating retrospectives but I am aware that some ways are better than others, which is why I wrote the book.

The thing about feeling safe in a retrospective is really important because the point with the retrospective is that, as a team, you should share and appreciate, and learn from what has happened. If you don't feel safe, you might not want to share the things that didn't go very well. Because maybe you want to cover up that something went wrong, you made a mistake, or you were afraid, or sad about something somebody said. Also, it's very difficult to appreciate what happened. And with appreciate, I mean, both appreciating in the positive and negative sense, acknowledging that these things happened and it actually didn't make us a better team. I think you're not really able to acknowledge that in honest unless you have the safety.

Then the last thing about learning, I think it's really important to learn to feel safe. That's also something that I apply a lot when I'm teaching at the university is that if the students don't feel safe to ask questions, if they don't feel safe to say that something they don't understand, then it's very difficult to learn.

John LeDrew: That's really interesting. So there's a couple of things that stuck out there for me. The first one around being, kind of, comfortable almost being uncomfortable. That's something that I really, certainly in my own practice, when I'm delivering retrospectives.

Anyone that has been in a retrospective that I've facilitated, I think in the last four or five years will testify to this is that a lot of the practice is actually creating safe discomfort.

In fact, a nice story is I delivered a retrospective where I'd done a game called animal lineup at the beginning. This game involves asking everyone as they come in the room "Think of an animal, along with a sound and an action, but keep it secret for now." And they will come in the room, obviously completely freaking out about what on earth this is gonna be about, what I'm gonna get them to do.

Then when they're in, you might have done some other funny safety check exercise first and they probably will feel really unsafe because you haven't told them what the hell I'm gonna do with this animal thing. I'll just say, you know, to their horror or I just want you to line up in order of your animal size. What I'd like you to do is that: the only way you can communicate is with the sound and the action that you came up with. Obviously, what happens then is hilarious because there are all of these interesting social things that happen. They all do it, even though they feel really uncomfortable because the majority will do it because it would be really uncomfortable for them not to. And they do it anyway. And they will get there.

Then you will have some people, kind of, walking around. I normally love seeing that somebody will walk up to someone and roar. They'll be replied to with another sound or something. At one point, I remember two people that, kind of, stood in front of each other going like this. I just wondered and said, "What's going on here?" And I said, "Well, we're just trying to work out what's bigger, an Indian or an African elephant." And I was like, "Tara, I'm amazed that you ever had any of that conversation going on. I'm guessing you now know what the context of this conversation is."

So after this had happened, it was very funny, lots of people laughing. Right at the end of the retro, we had actually had quite an interesting conversation where one of the team members had given really good but quite difficult feedback to somebody else on the team. Specifically, they had made jokes that made a lot of other people feel a bit uncomfortable. That had what was actually a direct but very respectful conversation about this in front of the team. Afterward, I'm clearing up and one of the guys comes up to me, this old dude who's this guy in his mid-50s, “Well, I don't know, in European measurements, but he's about 6'8", which I think is, you know.

Aino Cory: That's tall in European measurement. That's tall.

John LeDrew: Yes, very tall. Yeah. Even by European standards, even by Scandinavian standards.

Aino Cory: We would call it tall.

John LeDrew: Yes. That's the exact European standard. He's this very kind of tall guy from Essex and he just goes, "God, John, these retros, they're almost emotional by this." And he goes, "But I guess once you pretended to be an elephant in front of your peers, anything else goes, right?" And I remember thinking, after we spoke about it, I was like, "That's absolutely right," which is what actually seemed to happen was that, what we ended up creating with some of these silly games. I know we've both done, kind of, similar warmup style exercises at different times are that you create these situations that are really uncomfortable, but perceived as being really socially risky. But actually, they're not. It's like they're not really risky at all because everybody does them. But what you end up doing is by the time they come back to something that feels really safe in comparison, just giving feedback. It's like, which is actually something genuinely socially risky, which is what I find funny, giving direct feedback is really socially risky.

Aino Cory: It's something else there.

John LeDrew: But by that point, it almost feels safe now in comparison to pretending to be an elephant.

Aino Cory: Yes, that's true.

Key takeaway 1

Without psychological safety in a retrospective, the team will not be able to share, appreciate and learn.

Handling failures during a retrospective

John LeDrew: I don't know whether or not you've had a similar experience with, kind of, exercises or noticing that change in behavior when you do some little exercise.

Aino Cory: Yes. I have several of those. But as you know, since my book is about anti-patterns, I prefer to talk about my failures. As it turns out, everybody else thinks is more fun anyway. So, I'm definitely on board with having them do weird things and answer weird questions. I explain to them that it's because I want to build trust. If they build a relationship with each other, that's a huge element of trust to build that relationship. But one of the things that I remember that failed utterly for me is that I once had them as a new team of men, an IT company, many years ago, and the retrospective had been sort of negative. They'd been focusing very much on negativity, which, I mean, is understandable because they wanted to learn. But I think it's also a good idea to focus on the positive things that you want to do more of. But they had been a bit negative.

So I thought, in the end, I would sort of cheer them up by having the appreciation game. So I made them all stand in a circle, and they didn't really like to stand in a circle, because they thought, "Well, that's really weird." But I made them stand in the circle. Then I had a little ball with me, and I threw the ball to some of them, and then I said, "So this is an appreciation game. So I throw this ball at you. And I appreciate you for something that you said earlier, which I think was great. And now you, you look around and you find somebody in your team that you want to appreciate, and then you say that appreciation, and you throw the ball. It could be, 'Thank you for helping me at that time. Or thank you for always saying good morning, or thank you for that delicious cake, or thank you for that court review,' or something, anything. It could be anything."

And then the man who caught the ball, he sort of looked at the ball, and then he looked around at everybody else in the circle, and then he looked at the ball again, and then he just dropped the ball on the floor. That did not create psychological safety in that retrospective. I think that if it had happened now, I would have done something about it. But back then, it just really made me frustrated, and sad and feeling really bad at facilitating retrospectives.

So, sometimes these activities and games can also fail miserably. I think it's also important to say that to facilitators who are not that experienced yet. You hear us making all these interesting, funny games, but sometimes they fail. And it's important to know what you do then. How do you get something out of that as well? How do you get on? How do you move on from that? And also, sometimes they hear about a game or an activity and they want to do it because John did it or Aino did it but if they don't really believe in it, then it doesn't really work for them, right? So you really have to believe yourself that it's a good idea to make them say an animal sound and an animal activity.

John LeDrew: It's an interesting question that, like, how much of navigating our way as facilitators out of, let's just say, challenging situations like that? But how much of that is something that we have to experience? I've had difficult individuals, frustrating situations, situations that I was able to navigate out of, and situations that I didn't know, I just walked out of, leaving the team. Who knows? Probably. But in that era of continuous learning, I don't think that I could do... I think I learned from every single one of those. Like, I needed that massive discomfort of standing there with... For me, I remember it was a team member. We were just doing a simple check-in game, say any two words to check-in. And the team member, he said, "Retrospective ROI."

Aino Cory: It's a good start, isn't it?

John LeDrew: It was, actually. I just, like, "Wow, this is gonna be a great one."

Aino Cory: Yes, well, I sometimes ask the people at the retrospective, "So what do you expect to get out of the retrospective?" And then sometimes if they say, "I don't expect to get anything out of this retrospective," I'm like, "Oh, that's wonderful. You're making my job so easy. If you don't expect to get anything out of it, that's easy for me to accomplish definitely." So trying to turn it into, like, a joke, I think works as well, sometimes. I agree with you to an extent that it's difficult to learn from other people's mistakes, which is, everybody who's been a teenager knows that you cannot learn from your parents’ mistakes. You have to do them yourself at least one time. And yes, that’s why I did write this book about anti-patterns, which is to make people avoid doing my mistakes.

I think that what you can get out of hearing about other people's mistakes is maybe that you're aware that they're there and perhaps you can do something at least to avoid or at least be recognized when you're there. But also, I think, and this is important to know that other people, even experienced retrospective facilitators, have been in this situation. You're not the only one. It's not because you are tremendously stupid or bad at facilitating. I mean, it could be, but that's not why necessarily these things happen.

John LeDrew: I think that, to me, the interesting thing that I got from... I mean, maybe this is just from the same perspective as you in many ways because I think as I was going through it, I was just thinking, "Oh, yeah, I remember doing that. Oh, yeah. Yeah"

Maybe it is just a book. You know, the funny thing is I didn't see it as a book of your mistakes when I was reading it. I didn't. I just read it as a book of my mistakes.

Aino Cory: It's okay.

Key takeaway 2

Making and sharing mistakes is an important part of the learning process.

The retrospectives’ anti-patterns vocabulary

John LeDrew: It is fairly easy. No, but what I mean is, I was reading it through more as seeing the, "Oh, I remember that situation." And then it was interesting to see how somebody else navigated their way out of that. Yes. Like, it's interesting seeing situations... Things like the peekaboo problem. You know, people not turning their camera on, which is such a big problem, for right now and has become more of a challenge recently. Interestingly, lots of people when we have people that were remote on the particular client that I'm thinking of now, where they were people remote pre-COVID, they would turn their cameras off. But actually, they would often turn them on pre-COVID if they were remote, whereas now it's much more challenging for me to encourage people. But I find that it's like interesting seeing those and, kind of, I just saw them, yeah, as, "Oh great. Something else for me to try," as opposed to that maybe that is just the perspective of somebody that can recognize those challenges.

Aino Cory: I think it makes a huge difference that you are as or even more experienced in facilitating retrospectives than me. I remember when "The Gang of Four" book came out, the one about the design patterns for object-oriented programming. You could sort of divide people into two groups. There was a group of people who did not have a lot of experience in object-oriented analysis and design programming and they loved it. They learned a lot from it. They were like, "Oh, wow, all these things we wanna try." And of course, and then they overdid it, right, and we had Singletons in every single design. Then there was the other group of people who were experienced with object-orientation and they said, "This is simple. This is trivial. We all know this before."

Because of that, I'm happy that my book comes now 30 years later because now people have... I hope people appreciate that even if you read something in the book that, you know, it can be worthwhile to have a vocabulary to talk about it. Now, you said peekaboo and all the different names of the anti-patterns, I think are important because if people can talk about it, they can talk about things at a higher level of abstraction. I can say to you, for example, that I ran into some personal problems a few weeks ago, and I was... You know, sometimes when things just pile up on your head and you think, "Oh, there's this, and there's this, and there's this, and there's this," and you feel so small and dark, and insignificant, and stupid, and without any energy.

Then my husband said, "Isn't there something in the book that can help you?" I was like, "Oh, yeah, I'm in the soup. That's where I am. I'm in the soup. Both feet well planted in the soup." And I use the exercise, which is in the book, which I didn't invent, but it's in the book with the three circles about what you can do, what you can sort of influence, and what you just have to learn to live with. That helped me, not out of my problems, but out of my sort of reaction to the problem. So, I liked that we have been able to communicate it. Now when I say that to you, you understand what I mean.

John LeDrew: That's a really interesting point, actually. Our mutual friend Linda Rising, she's also quite a big fan of patterns.

Aino Cory: Yes, you can say that.

John LeDrew: Yeah. Pattern fans. Many of our conversations have spiked the idea that the real value in patterns is that being able to give a name to something. It's funny actually, how, you know, the old programming joke of, you know, the hardest things, whatever it is the three hardest things are naming things, cache invalidation off by one error to retrospect.

Aino Cory: So, it was important for me to find good names for these. Some of the names just popped up because it was the way that I thought about all these problems. But some of the names I had to think about, but I'm not entirely sure that all the names are good. What I felt was important as well in the book is that for every anti-pattern, I have like this little illustration with the red octopus. I had an illustrator, Nicole, who did this for me. The reason why I wanted these illustrations is that in my teaching, I've learned now that some people react to text verbally, and some people react visually. And if you're talking about a computer program, then a UML diagram is good for some people and the code is good for other people to communicate that. Obviously, you need the code at some point, right? But that's why it was so important for me to have an illustration for each of the anti-patterns. Because for some people, that will be the thing that sticks, that will be the way that they remember how to get out of this situation.

John LeDrew: I think that I really love the illustrations.

Aino Cory: I do too.

Key takeaway 3

The book creates a vocabulary for the most common mistakes (which we all make).

Stay tuned for the next episode "How to Avoid Failure in Your Retrospective".